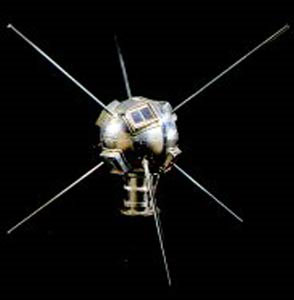

Amazingly, Project Vanguard, the first satellite powered by solar, launched in 1958. It’s the longest orbiting man-made satellite and is still orbiting the Earth! Once scientists figured out that solar was the best way to power satellites, manufacturers were able to gain a toe-hold, foreshadowing today’s modern solar industry. Vanguard I is tiny – it weighs about 3 pounds and is 6 inches in diameter.

Read our companion article, 1955: Why the US Chose Nuclear Energy Over Solar.

—-

By John Perlin

Few inventions in the history of Bell Labs evoked as much media and public excitement as the silicon solar cell, known at the time as the Bell Solar Battery.

The details about this invention Bell disclosed at a press conference the company held in April 1954 greatly boosted interest in solar energy. John Yellott, a mechanical engineer who probably knew more about twentieth century attempts to use the sun’s energy than anyone else in America, hailed the silicon solar cell as "the first really important breakthrough in solar energy technology." In fact, according to a 1955 Newsweek report, many foresaw the solar cell’s development as an eventual competitor to atomic power.

Technical Progress Continues in the Lab

Technical progress continued and in the next 18 months, cell efficiency doubled. But commercial success eluded solar cells because of their prohibitive cost. With a 1-watt cell costing $286, in 1956 a homeowner would spend $1,430,000 for an array of sufficient size to power the average house. This led to a sober assessment – however exciting the prospect is of using solar converters for power, clearly we have not advanced to where we can compete commercially, said researcher Daryl Chapin.

Hoffman Electronics, owner of the license to commercialize the Bell solar cell, begged to differ. CEO Leslie Hoffman saw its future in powering electrical devices in areas distant from electrical lines. "Consider," he told a gathering of government officials, " a remote telephone repeater station in the middle of the desert. An array of solar cells and a system of storage batteries is the answer. The option is to rely on heavy expendable dry batteries or fuel from a rather unreliable gasoline engine charging unit at great expense. The solar cell, he emphasized, "is a much better answer."

Silicon Atomic Battery Temporarily Eclipses Bell Invention

These officials, like most Americans, however, saw their salvation in a different type of power system – the atomic battery.

RCA, Bell Lab’s rival, had come up with a nuclear-run silicon cell, hoping for a perfect fit with America’s emerging infatuation with the atom. Instead of using sun-supplied photons, the atomic battery allegedly ran on photons emitted from strontium 90, one of the deadliest radioactive materials.

RCA made a dramatic presentation at its Radio City headquarters in Manhattan. David Sarnoff, founder and president of RCA, whose initial claim to fame was being the telegraph operator who tapped to the world: "the Titanic has sunk," hit the keys of a facsimile powered by the atomic battery to send the message "atoms for peace."

What RCA did not tell the public was why the venetian blinds had to be closed during Sarnoff’s telegraphy. Years later one of the lead scientists in the atomic battery project revealed RCA’s dirty little secret: had the silicon device been exposed to the sun’s rays that afternoon, solar energy would have overpowered the strontium 90.

And if the strontium 90 had been removed, the battery would have continued to work on solar power alone!

The director of RCA Labs didn’t mince words when he ordered his scientists to comply with the ruse, telling them, "Who cares about solar energy? Look, what we have is atomic energy at work. That’s the big thing that’s going to catch the attention of the public, the press, the scientific community," despite the fact that the Bell Solar Battery outperformed its atomic rival by a factor of 1 million.

And right he was. The government persuaded Americans, with the help of the media, to dream of the day when their homes, cars, locomotives, and even airplanes would run on radioactive waste produced by nuclear reactors.

The Illustrated London News chimed in, calling the atomic battery "a revolutionary invention." With this in mind, who needed the sun?

Alas, powering novelty items such as toys and transistor radios turned out to the Bell Solar Battery’s only commercial success. Martin Wolf, one of the scientists devoted to photovoltaic work, recalled a company display "where under room lighting, toy ships traveled in circles in a children’s wading pool. The model of a DC-4 with four electric motors turning the propellers was powered exclusively by a solar cell embedded in the wings. With the Bell solar Battery used solely for playthings, much of the initial enthusiasm generated by the Bell discovery soon waned.

Bell Solar Battery Finds Place in the Sun

Bell Lab’s Gordon Raisbeck wrote, "Very likely the solar battery will find its greatest usefulness in doing jobs the for which we have not yet felt."

Dr. Hans Ziegler, a power expert for the US Army Signal Corps who was sent to Bell Labs to evaluate the new device, came to a similar conclusion. After months of extensive discussions, he and his staff found one application in particular where the solar cell made a perfect fit for a top secret program – the development of an artificial satellite.

Freed from terrestrial restraints on solar radiation – namely, inclement weather and nighttime – "operations above the earth’s atmosphere would provide ideal circumstances for solar energy converters," the Signal Corps believed. Silicon solar cells theoretically would never run out of fuel since they ran on the sun’s energy.

The other power option – batteries – would lose their charge in two to three weeks. The modular nature of photovoltaics also meant that cells could be tailored for the exact weight or bulk. A tiny array could provide the small amount of power that transistorized communication equipment on board a satellite needed, without encumbering the payload. The Signal Corps concluded, "For longer periods of operation and limited allowance for weight, the photovoltaic principle appears most promising."

The secrecy of America’s space plans ended on July 30, 1955, when President Dwight Eisenhower announced America’s plans to put a satellite into space. A drawing that accompanies Eisenhower’s front page statement in the New York Times showed it had a solar power source.

The civilian scientific panel overseeing America’s space program saw powering satellites with photovoltaics as immensely important, since relying on batteries automatically condemned most of the on-board apparatus to an active life of only a few weeks. They noted that "nearly all of the experiments will have enormously greater value if they can be kept operating for several months of more" and decided it was "of utmost importance to have a solar battery system on board."

Based on the panel’s recommendations, the Signal Corps was asked to take responsibility for designing a solar cell power system for the program, called Project Vanguard. Its staff readily developed a prototype that clustered individual solar cells on the surface of the satellite’s shell. The group designed the modules to provide "mechanical rigidity against shock and vibration and to comply with thermal requirements of space travel."

To test their reliability in space, the Signal Corps attached cell clusters to the nose cones of two high altitude rockets. One rocket reached an altitude of 126 miles, the second 192 miles, both high enough to experience the vicissitudes of space.

"In both firings, the solar cells operated perfectly," Ziegler reported to an international conference on space activity in fall, 1957. A US Army Signal Corps press release added, "The power was sufficient for satellite instruments and they were not affected by the temperatures of skin friction as the rockets passed through the atmosphere at more than a mile a second."

Project Vanguard: First Practical Use of Bell Solar Battery

The first satellite with solar cells aboard went into orbit on St. Patrick’s Day in 1958. 19 days later, a headline in the New York Times revealed: "Radio Fails as Chemical Battery is Exhausted: Solar-Powered Radio Still Functioning."

Celebrating the first anniversary of the Vanguard launch, Signal Corps let the public know "the sun-powered Vanguard is still faithfully sending its radio message back to Earth."

By July 16, 1958, of the four satellites in the sky only the solar-powered Vanguard and Sputnik III – which was launched after Vanguard and also had solar cells aboard – were still transmitting. Both proved far more valuable to science than the first two Sputniks – equipped with conventional batteries – which had been silenced after a week or so in space.

The success of Vanguard and subsequent satellites using transistors in tandem with solar batteries demonstrated the synergy between these two newly discovered semiconductor devices. The transistor allowed for miniaturized and long-lived electronics light enough for launchable payloads and reliable enough for an environment where future maintenance was not an option. Because the transistor had a low power draw, the surface of the satellite was sufficient for enough solar cells to provide the necessary electricity, guaranteeing the longevity required for practical space missions.

The success of the US and Russia with solar cells in space led Soviet space scientist Yevgeniy Fedorov to predict in 1958 that "solar batteries will ultimately become the main source of power in space." Events proved him right.

Those working on satellites came to accept the solar cell as "one of the critically important devices in the space program," since it "turned out to provide the only practical power source" for satellites within a certain distance from the sun. As Rear Admiral Rawson Bennett, chief of naval research, succinctly stated, "The importance of solar power is that satellites can play a valuable role in warfare."

Solar-powered satellites gave America precise knowledge of its enemies’ capabilities and intentions both on land and in the sky. These satellites could also guide sea-based ICBMs, which became powerful deterrents. The Soviets could no longer consider a knockout first strike, knowing the US could retaliate by sea. Another series of solar-powered satellites, called Vela Hotel, could detect nuclear explosions on the ground and in space. Their verification capability cemented the trust required for signing the nuclear test ban treaty, vital to the health and safety of our planet.

The urgent demand for solar cells above the earth by the military opened an unexpected and relatively large business for the companies manufacturing them. "On their own commercially, they wouldn’t have gotten anyplace," observed Dr. Joseph Loferski, who spent a lifetime working in photovoltaics.

Indeed, as the scientist Martin Wolf contended, "The onset of the Space Age was the salvation of the solar cell industry."

++++

John Perlin writes and lectures widely on the history of energy, and solar in particular. He’s an analyst at the Department of Physics, and Director for Implementation of Solar and Energy Efficiency at the University of California/ Santa Barbara.

This article is an excerpt from his book, Let It Shine: The 6000-Year Story of Solar Energy, published in 2013. Contact johnperlin@physics.ucsb.edu to purchase the book – a portion of the proceeds benefits the American Solar Energy Society.

Reprinted from Solar Today, the magazine of the American Solar Energy Society, March/April 2014.