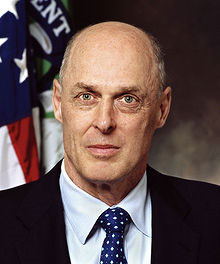

Hank Paulson, former CEO of Goldman Sachs and Secretary of Treasury under President GW Bush, wrote a compelling editorial in the NY Times this Sunday, comparing inaction on climate change to the financial bubble we experienced in 2008.

While at Goldman Sachs, the company made a big announcement for 2005 – that it would invest $1 billion in renewable energy projects and businesses, and promote LEED and Forest Stewardship Council certification standards. It also launched the Center for Environmental Markets, to research and develop pilot projects that inform public policy on market-based solutions to climate change, biodiversity restoration and ecosystem services.

In 2012, Goldman Sachs announced it would reduce carbon emissions to zero by 2020 and invest $4 billion a year for the next 10 years in green economy projects.

A conservationist, Paulson chaired The Nature Conservancy for two years. In 2011, he founded the Paulson Institute, which works on the premise that the "most pressing economic and environmental challenges can be solved only if the US and China work in complementary ways."

—

By Henry Paulson, Jr.

There is a time for weighing evidence and a time for acting. And if there’s one thing I’ve learned throughout my work in finance, government and conservation, it is to act before problems become too big to manage.

For too many years, we failed to

rein in the excesses building up in the nation’s financial markets. When the

credit bubble burst in 2008, the damage was devastating. Millions suffered.

Many still do.

We’re making the same mistake today

with climate change. We’re staring down a climate

bubble that poses enormous risks to both our environment and economy. The warning

signs are clear and growing more urgent as the risks go unchecked.

This is a crisis we can’t afford to

ignore. I feel as if I’m watching as we fly in slow motion on a collision

course toward a giant mountain. We can see the crash coming, and yet we’re

sitting on our hands rather than altering course.

We need to act now, even though

there is much disagreement, including from members of my own Republican Party,

on how to address this issue while remaining economically competitive. They’re

right to consider the economic implications. But we must not lose sight of the

profound economic risks of doing nothing.

The solution can be a fundamentally

conservative one that will empower the marketplace to find the most efficient

response. We can do this by putting a price on emissions of carbon dioxide – a

carbon tax. Few in the United States now pay to emit this potent greenhouse gas

into the atmosphere we all share. Putting a price on emissions will create

incentives to develop new, cleaner energy technologies.

It’s true that the United States

can’t solve this problem alone. But we’re not going to be able to persuade

other big carbon polluters to take the urgent action that’s needed if we’re not

doing everything we can do to slow our carbon emissions and mitigate our risks.

I was secretary of the Treasury when

the credit bubble burst, so I think it’s fair to say that I know a little bit

about risk, assessing outcomes and problem-solving. Looking back at the dark

days of the financial crisis in 2008, it is easy to see the similarities

between the financial crisis and the climate challenge we now face.

We are building up excesses (debt in

2008, greenhouse gas emissions that are trapping heat now). Our government

policies are flawed (incentivizing us to borrow too much to finance homes then,

and encouraging the overuse of carbon-based fuels now). Our experts (financial

experts then, climate scientists now) try to understand what they see and to

model possible futures. And the outsize risks have the potential to be

tremendously damaging (to a globalized economy then, and the global climate

now).

Back then, we narrowly avoided an

economic catastrophe at the last minute by rescuing a collapsing financial

system through government action. But climate change is a more intractable

problem. The carbon dioxide we’re sending into the atmosphere remains there for

centuries, heating up the planet.

That means the

decisions we’re making today – to continue along a path that’s almost entirely

carbon-dependent – are locking us in for long-term consequences that we will

not be able to change but only adapt to, at enormous cost. To protect New York

City from rising seas and storm surges is expected to cost at least $20 billion

initially, and eventually far more. And that’s just one coastal city.

New York can reasonably predict

those obvious risks. When I worry about risks, I worry about the biggest ones,

particularly those that are difficult to predict – the ones I call small but

deep holes. While odds are you will avoid them, if you do fall in one, it’s a

long way down and nearly impossible to claw your way out.

Scientists have identified a number

of these holes – potential thresholds that, once crossed, could cause sweeping,

irreversible changes. They don’t know exactly when we would reach them. But

they know we should do everything we can to avoid them.

Already, observations are catching

up with years of scientific models, and the trends are not in our favor.

Fewer than 10 years ago, the best

analysis projected that melting Arctic sea ice would mean nearly ice-free

summers by the end of the 21st century. Now the ice is melting so rapidly that

virtually ice-free Arctic summers could be here in the next decade or two. The

lack of reflective ice will mean that more of the sun’s heat will be absorbed

by the oceans, accelerating warming of both the oceans and the atmosphere, and

ultimately raising sea levels.

Even worse, in May, two separate studies discovered that one of

the biggest thresholds has already been reached. The West Antarctic ice sheet

has begun to melt, a process that scientists estimate may take centuries but

that could eventually raise sea levels by as much as 14 feet. Now that this

process has begun, there is nothing we can do to undo the underlying dynamics,

which scientists say are "baked in." And 10 years from now, will other

thresholds be crossed that scientists are only now contemplating?

It is true that there is uncertainty

about the timing and magnitude of these risks and many others. But those who

claim the science is unsettled or action is too costly are simply trying to

ignore the problem. We must see the bigger picture.

The nature of a

crisis is its unpredictability. And as we all witnessed during the financial

crisis, a chain reaction of cascading failures ensued from one intertwined part

of the system to the next. It’s easy to see a single part in motion. It’s not

so easy to calculate the resulting domino effect. That sort of contagion nearly

took down the global financial system.

With that experience indelibly

affecting my perspective, viewing climate change in terms of risk assessment

and risk management makes clear to me that taking a cautiously conservative

stance – that is, waiting for more information before acting – is actually

taking a very radical risk. We’ll never know enough to resolve all of the

uncertainties. But we know enough to recognize that we must act now.

I’m a

businessman, not a climatologist. But I’ve spent a considerable amount of time

with climate scientists and economists who have devoted their careers to this

issue. There is virtually no debate among them that the planet is warming and

that the burning of fossil fuels is largely responsible.

Farseeing

business leaders are already involved in this issue. It’s time for more to

weigh in. To add reliable financial data to the science, I’ve joined with the

former mayor of New York City, Michael R. Bloomberg, and the retired hedge fund

manager Tom Steyer on an economic analysis of the costs of inaction across key

regions and economic sectors. Our goal for the Risky Business project – starting

with a new study that will be released this week – is to influence business and

investor decision making worldwide.

We need to craft national policy

that uses market forces to provide incentives for the technological advances

required to address climate change. As I’ve said, we can do this by placing a

tax on carbon dioxide emissions. Many respected economists, of all ideological

persuasions, support this approach. We can debate the appropriate pricing and

policy design and how to use the money generated. But a price on carbon would

change the behavior of both individuals and businesses. At the same time, all

fossil fuel – and renewable energy – subsidies should be phased out. Renewable

energy can outcompete dirty fuels once pollution costs are accounted for.

Some members of

my political party worry that pricing carbon is a "big government"

intervention. In fact, it will reduce the role of government, which, on our

present course, increasingly will be called on to help communities and regions

affected by climate-related disasters like floods, drought-related crop

failures and extreme weather like tornadoes, hurricanes and other violent

storms. We’ll all be paying those costs. Not once, but many times over.

This is already happening, with

taxpayer dollars rebuilding homes damaged by Hurricane Sandy and the deadly Oklahoma tornadoes. This is a proper role of government.

But our failure to act on the underlying problem is deeply misguided,

financially and logically.

In a future with more severe storms,

deeper droughts, longer fire seasons and rising seas that imperil coastal

cities, public funding to pay for adaptations and disaster relief will add

significantly to our fiscal deficit and threaten our long-term economic

security. So it is perverse that those who want limited government and rail

against bailouts would put the economy at risk by ignoring climate change.

This is short-termism. There is a

tendency, particularly in government and politics, to avoid focusing on

difficult problems until they balloon into crisis. We would be fools to wait

for that to happen to our climate.

When you run a company, you want to

hand it off in better shape than you found it. In the same way, just as we

shouldn’t leave our children or grandchildren with mountains of national debt

and unsustainable entitlement programs, we shouldn’t leave them with the

economic and environmental costs of climate change.

Republicans must not shrink

from this issue. Risk management is a conservative principle, as is preserving

our natural environment for future generations. We are, after all, the party of

Teddy Roosevelt.

This problem

can’t be solved without strong leadership from the developing world. The key is

cooperation between the United States and China – the two biggest economies,

the two biggest emitters of carbon dioxide and the two biggest consumers of

energy.

When it comes to developing new

technologies, no country can innovate like America. And no country can test new

technologies and roll them out at scale quicker than China.

The two nations must come together

on climate. The Paulson Institute at the University of Chicago, a "think-and-do

tank" I founded to help strengthen the economic and environmental relationship

between these two countries, is focused on bridging this gap.

We already have a head start on the

technologies we need. The costs of the policies necessary to make the

transition to an economy powered by clean energy are real, but modest relative

to the risks.

A tax on carbon emissions will

unleash a wave of innovation to develop technologies, lower the costs of clean

energy and create jobs as we and other nations develop new energy products and

infrastructure. This would strengthen national security by reducing the world’s

dependence on governments like Russia and Iran.

Climate change is the challenge of

our time. Each of us must recognize that the risks are personal. We’ve seen and

felt the costs of underestimating the financial bubble. Let’s not ignore the

climate bubble.

++++

Here is the Paulson Institute website: