We wrote about Grameen Shakti back in 2003 and its mission to bring electricity to the poorest of the developing world in the most reliable and sustainable way.

Founded in 1996, Grameen Shakti is an offshoot of Grameen Bank, the pioneering micro-finance institution, which was established in 1976.

By 2002, Grameen Shakti had installed 11,000 PV sytems in homes, schools and businesses in Bangladesh. By the end of this year, it will have 1 million solar systems under its belt, with a goal of 5 million by 2015.

The nonprofit installs 1000 systems a day!

—

by Nancy Wimmer

In one of the poorest countries on the planet a renewable energy service company is installing one thousand solar home systems – a day. Not in its capital or busy urban centers, but where 80 percent of the population lives – in rural Bangladesh. The company, Grameen Shakti, literally translates as rural energy. By the end of the year it will have installed a total of one million solar systems and now has expansion plans to install five million systems by 2015. Shakti is succeeding where business as usual has failed, and in the year of Sustainable Energy for All, it’s a success story we should all know by heart.

As in other developing countries, the rural market is incredibly tough to serve and villagers are very poor. So how is Grameen Shakti selling them ‘expensive solar’?

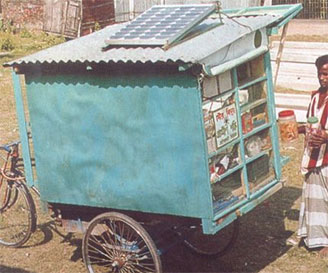

Shakti solved part of the problem by tailoring a solar system to exactly what people like the traveling food vendor, Mr. Majid needed: a 25W solar system to light his grocery cart and power his cassette player.

They then coupled tailored solutions with finance providing him with a loan he could afford to repay because he doubled his monthly income by working after dusk and attracting more customers with popular Bangla music.

But the problems don’t stop here.

Rural customers are hard to reach. In the Bangladesh delta of the mighty Brahmaputra, Ganges and Meghna Rivers it’s even tougher. Its villages can become islands in the rainy season, when almost half the country is flooded. Other regions where the land lies lower than the plains turn into huge lakes, forcing villagers to travel by boat seven months of the year. Serving village customers on the delta means traveling bumpy mud paths and crossing rivers – on foot, by bike, boat and by rickshaw. It can take hours during the rainy season to reach a few customers.

Shakti meets this challenge by creating rural supply chains and after sales service. Its engineers and technicians live, work and are trained on the job in the villages. They become part of the community, keep in close contact with their customers and make sure the solar systems are running. If there is a problem, Shakti is onsite to solve it – even in times of disaster.

In the aftermath of Cyclone Sidr, Shakti branch staff members were out doing repairs within hours in areas it took days and weeks for emergency teams to reach. For Shakti, all business is rural. Its field managers run 1,500 branch offices in every district in Bangladesh. They guarantee complete service – from installation, maintenance, repair and financing to customer care and training.

This focus on rural service began when Grameen was founded back in 1996. It sent bright, young engineers into the hinterland to set up its first branches. They won the trust of the villagers, trained local technicians, managed all financing, solar installations and maintenance. This laid the groundwork for Shakti’s quality service and steady growth, but it took years to develop.

Shakti has now set up 45 technology centers to produce and repair solar accessories. In this way production moves from the capital to the villages and solves problems of cost, logistics and rapid growth in a highly decentralized company.

The centers are managed by women engineers, who – like their male colleagues – live, work and train in rural communities. Of importance here is how these technology centers function as incubators for a further innovation: the village energy entrepreneur.

Kohinur, for example was trained at a technology center to become an energy entrepreneur. She earns an income producing and repairing solar accessories, is self-employed and receives ongoing support from the technology centers for her business. Neighbors now bring Kohinur solar lamps for minor repairs instead of contacting the Shakti branch. The technology center engineers supervise Kohinur’s work and do quality control.

Kohinur dropped out of school in the 8th grade, had no vocational training and no source of income, but is now able to contribute on average Taka 5,000 per month to her family’s income. This is as much as her father earns delivering fresh fish to the shipping port in Khulna and a substantial increase in monthly income for a poor family.

Kohinur’s story can be the story of the 1.3 billion people around the world without electricity access. But what we hear over and over again is that renewable energy technologies like solar are expensive and the rural poor are either too poor or too difficult to serve. The Grameen Shakti story explained in the book, Green Energy for a Billion Poor clearly shows how outdated and out of touch this line of thinking is.

With over five million villagers enjoying solar electricity and Shakti technicians installing one thousand solar systems a day it’s time our development institutions put their scarce development dollars behind initiatives such as these. No one can work miracles in a traditional rural society, but entrepreneurial companies like Shakti are proving we can do far, far better than business as usual.

++++

Nancy Wimmer is Director of microSOLAR and author of "Green Energy for a Billion Poor- How Grameen Shakti Created a Winning Model for Social Business."

This article first appeared in Compass, the Sierra Club’s blog.