In a miraculous reversal, almost all Little Brown Bats survived the winter in Aeolus cave in Dorset, Vermont.

Previously home to a hibernating 800,000 bats in this one cave, they have been decimated by white-nose syndrome since 2008. But this year, most of the small number left survived – and the same is true for two caves in New York, where the fungus first hit.

Last fall, biologists put radio tags on 440 bats and lined Aeolus cave with electronic equipment that monitors how many bats emerged during winter or spring.

"If we’ve seen that many bats pass through at the correct time, and behave what we would call normally, that’s really exciting," Alyssa Bennett, a biologist with the Vermont Department of Fish and Wildlife, told Associated Press.

Maternity colonies in Champlain Valley are thriving, and the population is increasing faster than it is declining, she says, but it’s not clear if young bats are surviving.

Running Its Course?

Could the fungus be running its course on its own? So far, scientists have been unsuccessful in finding a cure.

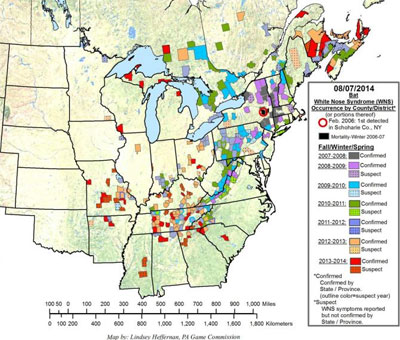

When white-nose first arrived, up to 90% of Little Brown Bats in Aeolus cave died that winter. Since 2006, more than 6 million bats have died as the fungus spread to 25 states and five Canadian provinces, wiping out seven species including Gray bats, Indiana bats, and bringing the once common northern long-eared bat close to extinction.

But since the NY and Vermont caves were among those first hit, it could mean that slowly, but surely, populations could rebound.

"In Vermont and New York and some of the places where white- nose has been for a long time, this many years into it, we’re not seeing as many visible signs of the fungus, the characteristic white nose, white powdery substance, which is the reproductive stage of the fungus," says Bennett.

Or could this slight recovery be caused by a behavioral change? One study found that those bats that survive are now hibernating a few inches apart, rather than huddling with other bats.

In this photo, the bat that’s alone doesn’t have white-nose, but those huddling do:

There’s no question the decline of what was once Vermont’s most common bat species has slowed, but it’s too soon to say little brown bats are recovering, she adds. Unfortunately, it would still take decades to see healthy populations because although bats can live for 20 years, they usually only have one or two offspring each year.

"We’re observing the most precipitous decline of a group of species in recorded history and it’s happening right here in our region," says Scott Darling, another Vermont biologist. "Several species, such as northern long-eared bats, have virtually disappeared in less than a decade and we are getting increasingly skeptical that they will ever be able to rebound."

White-nose doesn’t kill bats directly, it causes bats to awaken during hibernation. They leave the cave, expending precious energy trying to find food, and die from starvation from the lack of insects during the winter. During hibernation, bats’ immune system is suppressed so they can’t fight the fungus.

The fungus is common in Europe, but bats are immune. It inadvertently arrived here on the shoes or clothes of cavers who had been in Europe. The US Forest Service has closed all the caves in its southern region until 2019 and covered many others with disinfection mats to see if that kills the fungus.

Kentucky’s Mammoth Cave National Park – the largest cave system in the world – remains open to tours, but visitors’ shoes are scrubbed before leaving.

If bats in Europe can resist the disease, bats on this side of the Atlantic could also adapt, but can they do it before they are wiped out?

"I don’t know why these bats are still there, but I’m beginning to be a believer despite my pessimism that we are seeing something that is real and hopefully inheritable," Jeremy Coleman, white-nose syndrome coordinator for US Fish and Wildlife Service, told Associated Press.

Vermont has nine species of bats, six of which spend the winter hibernating in caves. In 2011, the state listed northern long-eared bats and little brown bats as endangered and added tri-colored bats in 2012. The US Fish and Wildlife Service listed the Indiana bat as federally endangered even before the onset of white-nose syndrome and has recommended adding the northern long-eared bat to the federal endangered species list. A decision is expected by October.

Bats can still be found in the attics of homes and barns, so if you see them there, consider them precious. Or think about putting a bat house up at your home.

In June, President Obama directed federal agencies to "reverse pollinator losses and help restore populations to healthy levels" of bees, birds, bats, and butterflies – as "critical contributors to our nation’s economy, food system, and environmental health."

Watch this 13 minute film, "Battle for Bats: Surviving White-Nose Syndrome," which shows how government agencies and conservation groups are working together to combat the fungus: